Design systems 101

Why use a design system?

Design systems establish organized standards that unify product teams by documenting a shared language encompassing product, brand vision, user experience, and visual design.

Design system standards enable design and development teams to adapt to change and scale products while minimizing confusion and redundancy.

The type of system depends on the product's needs, scale, long-term vision, and the team.

Is a design system different that a UI Kit or library of components?

UI kits and component libraries are tangible outputs of a design system. Other outputs include pattern libraries, layouts, usage and implementation guides, and content writing direction.

Design systems not only provide libraries of components but also context and direction around how the components are meant to be used within the product. Depending on the scale and scope of the system, foundations can also be incredibly become dense and require documentation and ongoing implementation support. Good examples of foundational scale could include dynamic language support, text and color accessibility needs.

UI Kits and Component libraries are highly specific while design systems are highly interconnected.

Foundations inform components, components inform layouts and patterns, and layouts and patterns inform product screens and flows. Design systems also involve a community of collaborative, interconnected people/contributors.

What are some outputs of a Design System?

Outputs in a design system depend on the product, the teams, and the existing or missing processes and materials.

Examples outputs in a design system:

Foundation library (Figma + code repositories)

Component library (Figma + code repositories)

Pattern library

Layout library

Icon library

Graphic/Illustration library

Usage guidelines

Implementation guidelines

Design tokens

Content management

Brand management (content tone of voice, visual direction, + asset management)

Contribution guidelines

Governance models

Design system architecture + mapping (or simply a mental model)

Product team support documentation + channels

Education + training materials

Design system reference site

Audits and workshops

Ways of working + processes

How is a design system different than a style guide?

Style guides are relics of print media, typically outlining a brand's color, typography, tone of voice, and design elements. They focus on how to use these assets effectively.

Style guides, though not originally intended for digital media, offer effective design systems for smaller product teams without complex components. They provide a solid foundation for developing a design system since they include essential documentation.

The fastest way to create a system is to document what you’re already using.

Style guides define color, typography, and provide examples, but this information alone lacks the context needed for effective AI tooling. Robust systems capture specific intent and context, guiding AI on how to use design elements effectively.

Resources + references:

How we utilized data to inform a navigation pattern redesign

Gathering and analyzing data

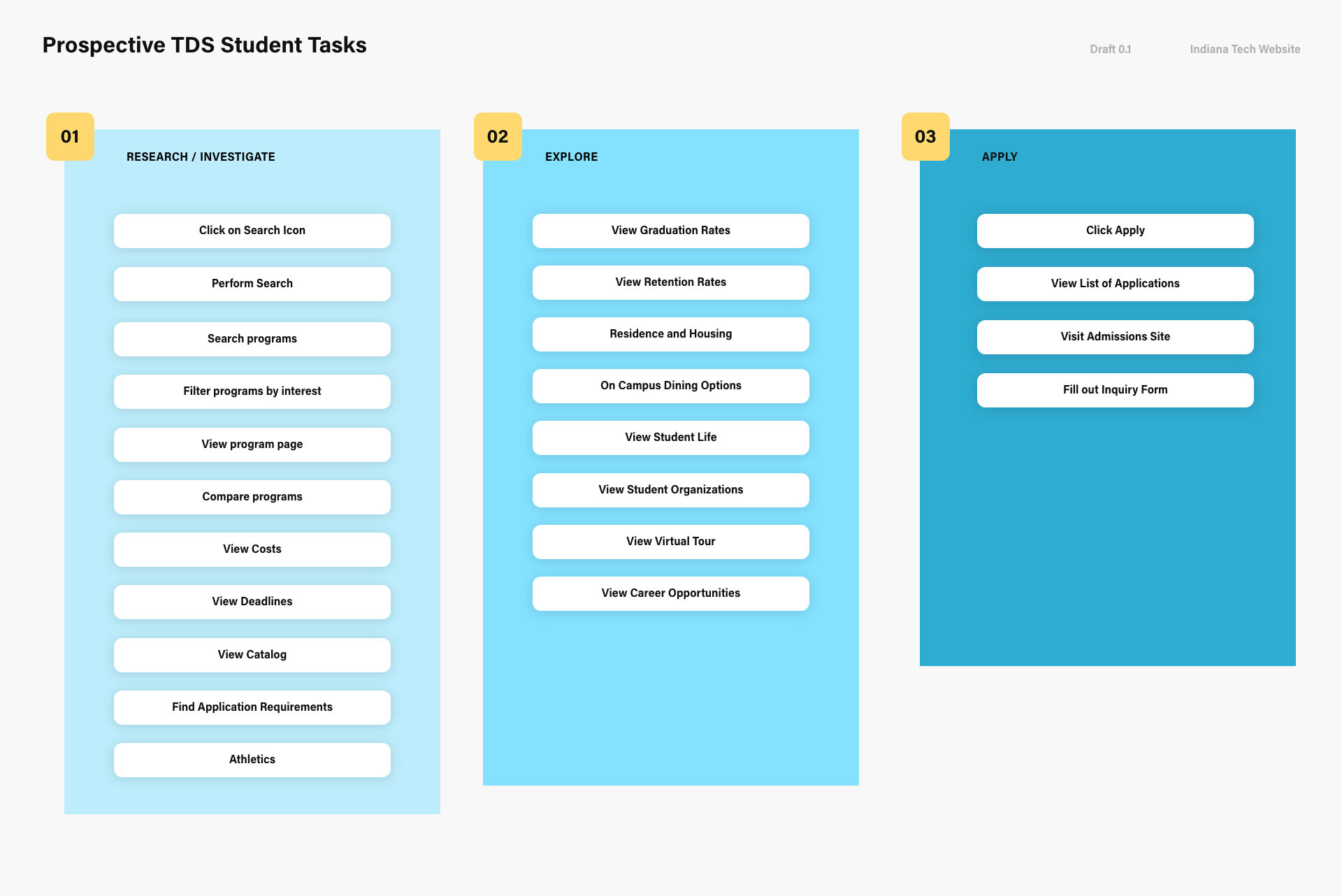

The first step in my design process was identifying the major user groups: Who is using our site? How are they currently using our site? What can we do to improve their experience?

I was able to identify key audiences through analyzing analytics and research. I scheduled regular interviews with stakeholders in various departments and conducted surveys with students. The research conducted by SimpsonScarborough provided great insight and direction.

The primary audience being our prospective students (traditional, non-traditional, grad/doctoral) and traditional prospective student parents. We have subsets as well within those major categories such as, athletes (traditional), international, employees (non-traditional), returning students and transferring students

The secondary audiences include our current traditional, non-traditional, and international students, alumni, faculty, and staff.

The last group includes high school guidance counselors, community, etc…

Stakeholders are also an audience I am mindful of, this includes the President, Board of Trustees, Vice Presidents, and various department leads.

Once the various audiences are identified, next steps in my process included analyzing analytics, heat maps and surveys. I investigated how the users were using our sites based on behavior flows, traffic, and heat maps. Information from my research guided my early drafts for the top level and interior department page navigation schemes.

I utilized card sorting exercises to help with identifying priority and organization “aka buckets” for the navigation. That information became the first draft of the sitemaps for the main and interior department navigation schemes. In this, I also discovered a need for some sort of quick link area that evolved into a dashboard.

Market Research

Understanding the market

Identifying competitors

Performing competitive analysis

Thinking about possible layouts and options.

Experimentation

We partnered with SimpsonScarborough to aid in our rebranding efforts. With their help we were able to gain insight into our brand and what it means to our audiences.

Competitors are a mix of both a market based on specific education delivery models and local universities. When organizing the list I kept in mind how prospective students would compare universities and the various needs of our different types of students. Indiana Tech’s online delivery model, The College of Professional Studies, or known as “CPS” for non-traditional students was what made Indiana Tech special among its competitors.

During my research, schools with very similar delivery methods of education included Arizona State University (ASU) and Indiana Wesleyan University are ones we focused on. Arizona State University is an indirect competitor, while Indiana Wesleyan, Indiana Purdue Fort Wayne and University of Saint Francis are direct competitors.

Competitive Analysis worksheet for feature consideration.

In my research, I found that many of our direct competitors did not make use of video often for their homepages. Many of our direct competitors used slideshows. Chat was rarely implemented as an option, student perspectives/stories were not always featured and dates/calendars were not common. Not included but noted, program specific searches were often more of directory instead of an interactive experience.

Primary Navigation Analysis

Similar to the competitive analysis above, I also ran one for navigation items. The chart below indicates common patterns and terminology with other universities. It’s important to review these to make sure we’re not missing the mark with what our users are expecting to find/or are used to finding.

I’ve noticed that in attempts to stand out and brand services we offer students, if we go too far from expectations, it only causes confusion. Below we can see some patterns in terms of what is considered higher level and should be featured in a primary navigation.

Top level navigation analysis.

I followed up with tree testing, card sorting exercises with small focus groups and preference testing. Below is the organization we ended up with. After some continued testing, we made changes to naming and hierarchy.

Top level/global navigation early sitemap draft.

Our site also did not feature any sort of drop down with the navigation. The information was hidden exclusively on the individual landing pages. Users were forced to commit to a page without knowing what would be on that page. We affectionately referred to these pages as “link dumps” because they would often cram as many links as possible in each section.

I found in user testing, this only overwhelmed our uses and caused confusion. The interaction cost was too great to hide all of the information on landing pages.

I was able to organize links through the activity data presented in our heat maps. The data influenced the various hierarchies on the department pages later on, helped create “actionable” information and helped inform the links we included in the navigation and dashboards.

Example of our Academics heatmap from 2016. I used the hotspots over time to help determine a hierarchy for what users were actually going out of their way to click on. The heatmap data combined with feedback influenced what I included in the dashboard designs later on.

Content Inventory and Audits

Determining our priorities with the navigation also helped when approaching the content on the site. Auditing and reviewing the content is an ongoing process with yearly scheduled reviews with editors. In the redesign, I initially kept most of the existing content with ongoing plans to review as I worked through the redesign.

The first step in reviewing the content was to create a site inventory. I made a spreadsheet and listed out all of our top level domains/subdomains on our site. From there, I created a catalog of topics and content already existing on the site and held meetings with the various editors of our site to encourage them to review their content regularly.

Our developer created an plugin on our site to help me and my editors keep track of how long content had last been updated or edited. Regular messages were sent out to our network of editors encouraging them to review/audit their content. I streamlined the editing process and maintained training for our editors.

Old Pages plugin built by Joel Kuhn, Web Developer at Indiana Tech.

Learn more about how this data informed the designs.